In 1980, Mt. St. Helens erupted. It is still considered an active volcano and is monitored carefully. It demonstrates to us how the earth can be transformed quickly by a catastrophic event.

We drove to the west entrance of the national monument on Highway 505. The wildflowers were blooming. This created a peaceful view of the mountain as we stopped along the way at a couple of viewpoints.

We tried to go to the end of the road to Johnston Ridge Observatory, but the road was closed for repairs. We could only go as far as Coldwater Lake. Apparently, the repairs are serious, in that, it isn’t expected to open until 2025. We stopped instead at Coldwater Lake where we found a picnic table to eat our lunch.

After lunch, we went to the Coldwater Visitors’ Center where we listened to a Ranger talk. From the deck we had a clear view of the mountain and Coldwater Lake where we had just been.

Coldwater Lake was formed after the eruption when Coldwater Creek was blocked by debris. Looking at the vegetation growing around the mountain, one wouldn’t suspect that anything catastrophic had happened recently. Coldwater Lake is clear and blue. But after the blast, it was filled with volcanic debris and vegetative matter. Though it took several months, bacteria in the water cleared up the debris in a very short time.

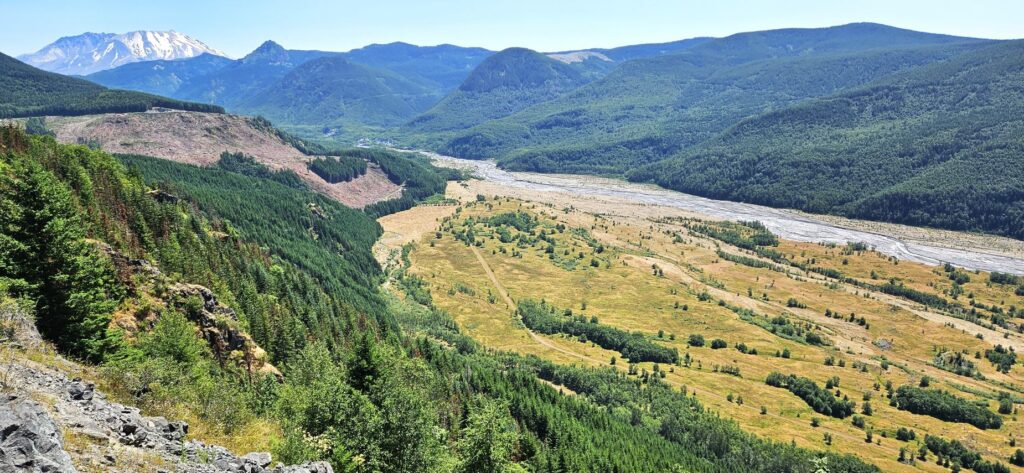

On our way out, we stopped at the Mt. St. Helens Forest Learning Center. From that viewpoint, we could see the debris channel where mud, water and ash flowed for several miles on the day of the eruption. Many trees have been planted in some of the blast areas. Today they are fully grown. Other areas were left alone to study the results of natural re-vegetation.

On another day, we drove to the backside of Mt. St. Helens to see Spirit Lake. The road there is an old forestry road. It is not bad, however, since it is paved the entire way. On that day, smoke from wildfires clouded the air.

All of the trees near the mountain were laid flat when the blast occurred. Only the areas in the shadow of the surrounding hills were left standing. The trees which were blown into the lake formed a mat that covered 40% of the surface. Today, there is still a small area covered by floating logs.

Mt. St. Helens had a very cone-like shape before the eruption. This is the side of Mt. St. Helens that was blasted away during the eruption. It is very easy to distinguish Mt. St. Helens from the other mountains around because of its altered shape.

The natural outlet to Spirit Lake was blocked and the lake rose 200 feet. A tunnel had to be constructed to maintain the lake’s depth at a constant level.

Although there is a trail up a ridge to see a better view of Spirit Lake, we opted out.

Wildflowers were abundant when we were there. Can you see the butterfly?

Looking the other direction at Spirit Lake, one can still see the area of destruction from the blast decades later. However, there is also plenty of plant life that has grown back, and wildlife that have come back to live there.

On our way back home, we spotted a very familiar mountain peak in the distance–Mt. Rainier.

On our flight to Austin from Seattle, we once again got a view of this magnificent mountain.

Although this eruption happened decades ago, I’m still amazed at how the land has recovered. It’s hard to wrap my head around how much force was exerted that day to blow away half of the mountain.

“The mountains melted like wax at the presence of the Lord,

At the presence of the Lord of the whole earth.” Psalm 97:5